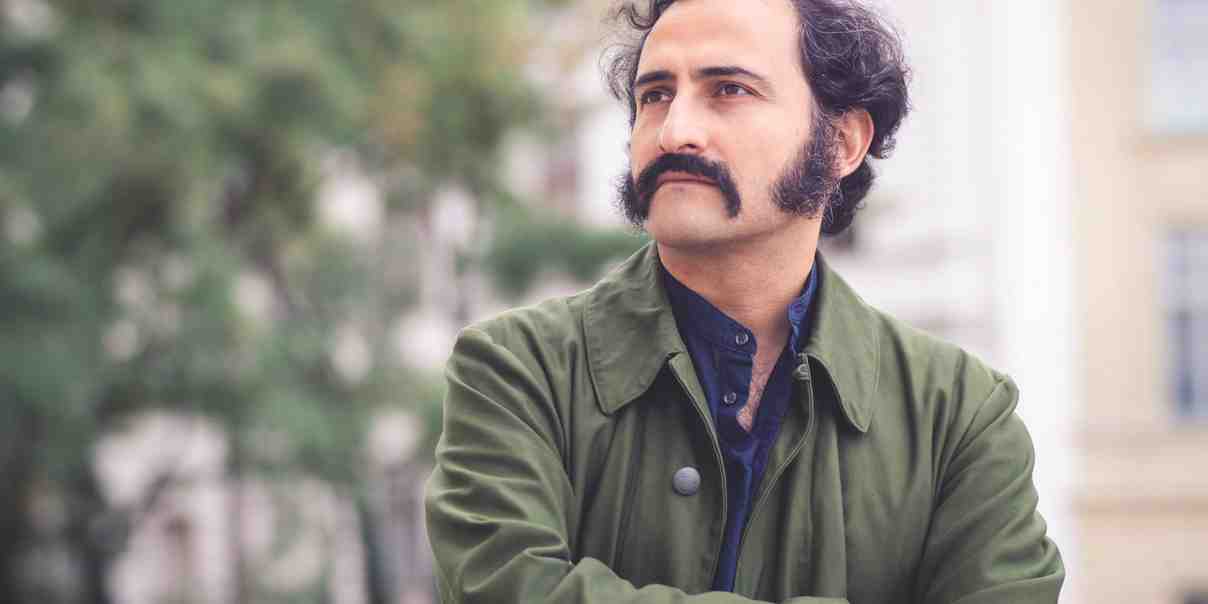

The Language of the Choir: A Conversation with Amir Gudarzi

Meet the Participants

Amir Gudarzi was born in Iran in 1986 during the Iran-Iraq war.

He later graduated at the only school for theatre in the country at that time and studied scenic writing in Tehran. Due to censorship, his plays were only shown in private circles. On the side, he wrote scripts for TV-series and feature films. Since 2009, Gudarzi has lived in involuntary exile in Vienna, Austria, where he studied theatre, film and media studies.

In 2017, he won the exil-DramatikerInnenpreis for his play Between Us and Them Lies … In 2018 he was nominated for the Austrian Hans-Gratzer scholarship of Schauspielhaus Wien, his play Arash//Heimkehrer premiered in Vienna and his performance The Knowledge Tree was shown in Jerusalem. In 2019 Gudarzi’s play The Assassin’s Castle was invited to the Berlin Stückemarkt. In 2020 Jelly man – The Future in between my Fingers premiered in Vienna and his piece Who cut the cake was shown in London’s Royal Court Theatre as part of the Living Newspaper project.

Gudarzi is nominated for the Austrian Retzhofer drama price 2021 with his play Wonderwomb and received numerous drama and literary scholarships, including 2018-2020 from the Austrian Chancellery and 2020/2021 from the Literary Colloquium Berlin. Amir Gudarzi lives in Vienna and is working on his debut novel.

A few months ago, PlayCo met for an interview with playwright Amir Gudarzi, the current writer-in-residence at the National Theater in Mannheim.

Born in Iran, Gudarzi has lived in Austria in involuntary exile since 2009. His debut novel, The End Is Near, was published for wide release by German publisher dtv last summer; this season his plays will see five productions in Austria and Germany. Gudarzi’s work is concerned with war, migration, and capital: Wonderwomb, which received the Kleist Förderpreis for dramatists, is narrated in part by choruses of dead animals who will become oil and products made from oil; The Assassins’ Castle follows a refugee of imperialist war in the Middle East on his arduous journey to Europe amidst orientalist fantasies and xenophobia.

Gudarzi draws from different classical texts: The Assassins’ Castle is framed by the story of Oedipus at the gates of Thebes, refers continually to Marco Polo’s “Old Man of the Mountain” legend, later picked up by the Crusaders, and quotes directly and extensively from the Epic of Gilgamesh. We started off discussing his process of selection—how did he arrive at the juxtaposition of these stories in particular?

“I’m just reading a lot,” Gudarzi says, “and sometimes there is a click in my mind.” At first glance, the connection between the stories might not be visible; he writes to make it so. Some of the people in Europe, he’s noticed, are often quick to dismiss what they label as “simple refugee stories.” But the path of the play’s refugee character, Another Him, is mirrored in the story of Gilgamesh—the oldest story in the world, although it’s less well-known in the West. Gilgamesh, two-thirds god and one-third human, travels over mountains and sea to find an escape from biological death; Another Him passes through the mountains of Turkey and crosses the sea to Greece, trying to escape from death caused by other humans. Oedipus, although far better known in Western countries, is also the story of a stranger trying to enter into a city and failing. The sphinxes at the gate mimic the border regime of fortress Europe. And Marco Polo, whose path is the inverse of the main character—West to East—ties in the colonial attitude endemic to Europe, an attitude which extends inexorably into the present. In the Marco Polo story, Gudarzi points out, we see war between Christians and Muslims. There is a religious narrative around Americans waging war on Iraq; with the Another Him character, we see histories repeating and overlapping. In connecting these disparate histories and ideas, Gudarzi tries to make possible a new interpretation. He describes this practice as “pointing with a light.”

Gudarzi writes in German, his adopted tongue. “It is a privilege to think in two languages—you have a lot of people speaking five, six, or just one language, but not thinking in them.” (He counts English as a language he can translate into in order to communicate, not one he thinks in.) Entering into one language from the vantage point of another can reveal the history that a language tries to hide: “Sometimes, when writing, I wonder: why is it not possible to express this thing? I’ll have Farsi words or expressions that I try to translate in my mind, and it’s not possible, and the same thing happens vice versa. And I think, oh, okay, it belongs to the history of the language. The language is hiding something. I am able to bring the language to speak what it’s trying to hide by stealing expressions from one tongue to another.” The epigraph of Assassins’ Castle is a quote from Paul Celan, the modernist Jewish-Romanian poet, who writes in German but contorts it in strange and brutal ways. Celan, in an award acceptance speech in 1958, said of language: “In spite of everything, it remained secure against loss. But it had to go through its own lack of answers, through terrifying silence, through the thousand darknesses of murderous speech.” The quote is about the Holocaust, which Celan survived, and about “the role of the German language in building this machinery of killing.” Gudarzi observes wryly that, when he sought refuge in a new language, perhaps German was not the best choice—its past is particularly bloody. But, he says, the process of learning to command it was “interesting to go through.”

It is precisely this violence of language that he tries to make apparent in Assassins’ Castle, which is haunted by a chorus of European “Voices” calling out couplets meant to discourage refugees: “Tell them that there is no room here / Don’t tell them that there is enough room here.” The chorus recites sentiments “that I hear in everyday life in Vienna, or Germany,” expressions of fear and hatred that have the power to “cut through the play” because, in many European countries, they come from places of power, constantly “cutting the process of democracy.” “At the beginning,” Gudarzi says, “there is a logical idea,” but the chorus becomes increasingly absurd and contradictory over the course of the play, its logic breaking down.

He’s also interested in the way choirs function in religious services, producing a polyphony of human voices that change depending on where the choir is standing. The church becomes a kind of theater. Gudarzi wants to incorporate new ideas into European theater, which is formally very conservative—theaters built a century ago, audiences always facing the same direction, etc. In Wonderwomb, as opposed to in most contemporary plays, the lines aren’t realistic dialogue so much as storytelling, framing the play the way a camera might in film. “Language is the motor of theater. Poetical language is something cinema can’t do. They produce poetical images with the camera. That’s what I try to do with language.”

The choruses are also important to Gudarzi’s plays because they present a kind of collectivity that’s increasingly repressed or forgotten. “We are going towards a new age where we’re told that personality is very important. They are making out of us only individuals—we look at ourselves; we are very selfish in a way. It is good to have personality, to have individual identity, but it is also something pushed towards us to kill solidarity as human beings.”

Gudarzi’s plays have never been produced in the United States, but he thinks they might actually see more engagement in a place like New York, where people come from all different backgrounds, as opposed to in the German-speaking countries where they’ve previously been performed. “I try to write for the whole world—not focused on Germany or Austria or so on. In Wonderwomb, I am talking about a cosmopolitan issue or topic. Why focus on only some countries when almost the whole world is in it? I need to write in one language, but I always had other people in mind, as well, in different parts of the world.” In Germany and Austria, however, “people are always talking about how open they are to the world, how cosmopolitan their thinking is, but it’s not true. They want characters talking only about issues in Germany.” When they hear “international,” Gudarzi says, they think of plays from other countries being translated into German; they don’t think of events in the world as interconnected—an ethos that is integral to Wonderwomb. The few people of color in past audiences of Wonderwomb saw more in it than audience members whose families had been in Germany for generations. Gudarzi had a similarly refreshing experience working in London, where the population is more diverse.

Gudarzi has described his plays as a “panorama of time.” He has a preoccupation with the past. In Wonderwomb, the generations of dead literally fuel the present, and the play gives them a voice. “I was doing research on everyday life rituals in different countries in Europe and Asia, and these rituals are all related to very old religions that have since been destroyed and vanished. Our way of living is actually made by the past,” by art and writing that through ritual and age acquires the gravity of myth and religion and becomes immutable. For example, “If we are talking about East and West, there is still war. After 9/11, people questioned, ‘Why do they hate us? Why are they attacking New York?’ But you have this war 2500 years ago between Greeks and Persians. We know the Western version because the Greeks wrote history; we don’t know the Persian history because it’s destroyed by time and conquerors.”

Gudarzi’s process involves “digging into small things” to try to find similarities with the present. “I am thinking about the past because I want people to understand that what we are doing is affecting the future as well. Talking about the future is difficult without a past.” In Iran, for example, where the dictatorship has gone on for almost fifty years, there is almost no science fiction about the future, “because people are still grappling with today and yesterday.”

“Human beings are very good at deleting or destroying the past. War always destroys the past and creates a new one—history in the Middle East always begins anew with each new king.” In Europe, on the other hand, the church’s overarching power allows it to function as an archive outlasting regime change. In Vienna, Gudarzi says, you can see a declaration of the state from five hundred years ago, or four hundred-year-old business records. At the Austrian Jewish Museum, there are scraps of fabric used as visas for Jewish people, whose movement through Europe was prohibited by antisemitic laws. “In the Near East,” Gudarzi says, “even eighty, seventy years ago, people didn’t have birth certificates; they passed freely without borders or identities. You don’t know who was in your family three generations before. But in Austria, the state is like a bureaucratic monster, knowing everything about people.” You can see records of birth, death, religion, and marriage for hundreds of years in church records. Even poor people have a registry, since the church got money from them, too. Europe has destroyed the whole world, remade the history of the colonized in the wake of its wars—but its internal records are carefully preserved. Still, stories like the Epic of Gilgamesh were translated into Greek, copied in episodes of the Bible, something we know due to the original text of the Epic having been found in cuneiform script. They exert an influence on European culture that Europeans are often unaware of.

At once concrete, sharply political, and allegorical, Gudarzi’s plays illuminate history’s barbarism and its silences, revealing a world that is inextricably intertwined by stories.

Written by

PlayCo Staff