On Etan Patz and Walking to School

Etan Patz disappeared forty years ago, on May 25, 1979. I was seven then, in second grade, and right around that time, perhaps even that same month, is when I started walking home from school on my own. We lived on 4th Street and Avenue A, maybe three quarters of a mile from Grace Church School, on 4th Avenue and 11th Street. Previously, I had been picked up and dropped off by a school bus. One of my school mates lived in Chinatown, and the driver or drivers (there may well have been regular turnover) often got lost. I remember the bus circling around and around, up and down avenues and smaller streets as the sun set.

I understood the school’s geographic relation to my home, and that Manhattan was a grid. On that first day I simply walked out the school’s front door and headed south, from 11st Street past Cooper Square, down to 4th Street and the Bowery, where I turned left, and walked home to Avenue A. I don’t know how my parents felt about my assertion of independence, but they came up with a plan. I would be able to walk home on my own on certain select days that spring, and starting the next fall, once I was eight and in the third grade, I would be able to walk to and from school every day.

Etan was just six when he disappeared. He wasn’t walking far, just to the end of the block. By six, I was out on my own some too, both down to the playground next door to our apartment, and around the corner to the newsstand to buy my mother True Blue 100’s and a Milky Way. My mother, when she wasn’t working, liked to stay in bed and have errands done for her. Her sisters called her “the queen.” Parenting-wise, she was a product of the seventies, and practiced “benign neglect.” Aside from reading, which was her big obsession (we spent a lot of time with D’Aulaires’ Myths), I had a great deal of freedom to do as I wanted, and spent a lot of time by myself.

Soon, I had my own special route to and from school. I came up with it on my own, rarely deviated from it, and remember it to this day, a zig zag route past various landmarks, known only to me, and small shops where I could buy candy, soda, or pizza, and play arcade games. Most of my friends started going on their own to school around that age too. Brad walked from Washington Square with Dean, a bigger kid who lived in his building. Charlie, the son of a single mom actor, walked from Stuyvesant Town, though apparently she followed him, clandestinely, for months, to make sure he was crossing streets safely. Steph and Alex, fraternal twins, walked from West Broadway in Soho, just around the corner from Etan’s family. Many decades later, I was to learn from Steph that he and Alex had known Etan and attended the day care center that his mom Julie Patz had run out of the family’s loft.

As the years went on, our freedom only grew. We went further afield, visiting different neighborhoods, traveling by bus and subway. By seventh grade, we were finding our way to Mets games in Queens. It wasn’t all good. I was mugged twice on my very own block. Once, while playing in the playground, I had my watch taken, and while walking to school one morning, I lost five dollars. The specter of Patz remained a presence in our childhoods, a boy whose name and story we all knew. And I get the sense that my parents talked some about his disappearance too. I remember my mother saying that she would “kill” anyone who hurt me. Within a couple of years, the faces and names of missing kids were visible on the backs of milk cartons. I looked carefully at those children, trying to remember their faces, just in case I happened upon one of them while walking down the street. Etan too, I kept an eye out for. I wanted to think that he’d found a new life somewhere, and would someday get to return to his family. The alternative was unimaginable.

I don’t think I ever fully let go of that notion, because when Pedro Hernandez was arrested for the boy’s murder in 2012, I was surprised and somehow uncomfortable. After the arrest, I looked at photos of the boy and was shaken anew by his striking brown eyes, and dirty blonde hair. In 2015, New York Magazine published a candid photo, taken by Carrie Borretz, then an intern for the Village Voice, in 1975. She’d rediscovered the photo decades later while combing through her work in preparation for a book. Three-year old Etan is in a stroller pushed by his mom, with a few other kids around him. Looking at that photo now, I see both myself in the 1970’s, and also my four-year old daughter Delphina. Being a parent makes one think the unthinkable.

Delphina has never been out of our apartment on her own. She will run ahead to the front door within our housing complex, but she is always within eye sight. Once, because she insisted, I left her upstairs in our apartment, while I took the elevator to the lobby to change the laundry. As I was moving the clothes to the dryer, my mind went to all sorts of awful places. Had she turned on the stove, and hurt herself somehow? Would something minor happen that would get the city involved? Would they take her away from us? When I got back upstairs a couple of minutes later, she was sitting in the living room, playing, just as I had asked her to do. She is a child who follows directions, mostly. When she runs ahead on the sidewalk, she stops well shy of the curb. I am glad for her cautiousness. It tempers my fears.

I still live on 4th and A, in a middle-income housing complex just across the street from where I grew up. And Delphina, as I did in 1975, attends junior kindergarten at Grace. Most mornings, I walk her there, often along the route that I took. “There’s the whale, and the turtle…Here’s the Indian restaurant block. Let’s count to see how many are left…There’s where the old punk guy with the cane stood, in front the Te-amo smoke shop that used to be there, on St. Mark’s Place and Third Avenue.” We make our way through my memories, my urban palimpsest. Ostensibly, this narrative keeps Delphina focused and moving forward during the fifteen-minute walk, as we always have a next place, nearby, to get to, but mostly I do it for myself. It gives me enormous pleasure to remember these streets. Walking to school on my own is one of my best memories of childhood. That freedom and independence, the ability to have ownership over my own experiences, allowed me to discover myself. It helped me to grow up.

These days, young children rarely walk to school on their own. Before sixth grade, many schools require that special permission be given before they’ll let a child arrive or depart on their own. My friends Shawn and Kate have been letting their nine-year-old son Jason walk in the mornings on his own, up from Houston Street to 12th Street, along Avenue B.Special permission was indeed required. It seems they are the only parents in their grade making this choice. As I was writing this essay, I received notice of a state mandated lockdown drill at Grace. The kids call it a “huddle drill.” In this age of school shootings, I understand why this may need to happen, but the fact of it still makes me sad, and angry. I sense that it comes with a cost. The fear that gets transmitted has impacts, both short term and long. I want, of course, to keep my daughter safe, but I also want to raise her to be independent and brave, and that will involve some risks and struggle on her part to figure things out for herself, and, on my part, to let go.

And yet, rational or not, the unthinkable for me remains. I know that stranger abductions are incredibly rare, that she, or we, are more likely to die in a plane crash, but nevertheless the fear that it engenders in me is physically palpable. My daughter, nearly five now, will certainly ask for opportunities to be independent. And I hope to put aside my fears, and say yes to her requests. I don’t think I’ll be letting her walk to school at seven, like I did, in 1979. But I do think she’d be capable of it. She is good at “looking both ways,” always takes my hand before we cross the street, and gets mad at me if I don’t wait for the light. I do hope to send her down on her own to the playground within our housing complex soon, or around the corner to buy a smoothie. And hopefully, by the time she’s nine or ten, she’ll be walking to school on her own. I am inspired by Shawn and Kate, and have been hearing from them about how well it’s been going for Jason. Mornings used to be hard, but now he is up earlier, and gets himself ready to go quickly so that he can be out the door and on his way before Shawn or Kate walk his little sister Hailey to school. Soon enough, I would imagine, Jason will walk Hailey, and they, together, will build childhood memories. Delphina, too, will build memories here, discovering her own stores, and landmarks. She’ll build a personal map of this neighborhood and these streets, a world of her own that I may never come to know. That undertaking feels like an essential part of growing up.

“On Etan Patz and Walking to School” was published March 17, 2019 on Mr. Beller’s Neighborhood.

Related Productions

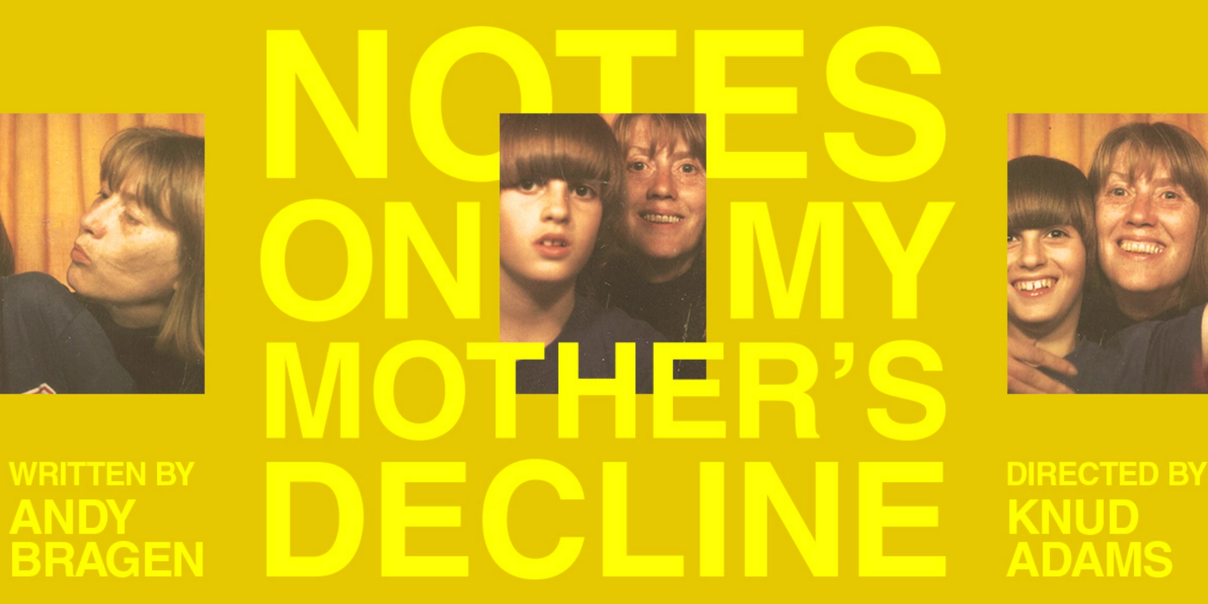

Written by

Andy Bragen

About the Essay

NOTES ON MY MOTHER'S DECLINE playwright Andy Bragen is a native New Yorker hailing from the Lower East Side. He recently published his essay “On Etan Patz and Walking to School” in the online journal, Mr. Beller’s Neighborhood. In his essay, Bragen reflects on his childhood neighborhood where he still resides today with a family of his own. While some things about his home neighborhood remain unchanged, he has found himself growing with the city and with the normal concerns of any new parent.